Solidarity Poiesis

Solidarity Poiesis

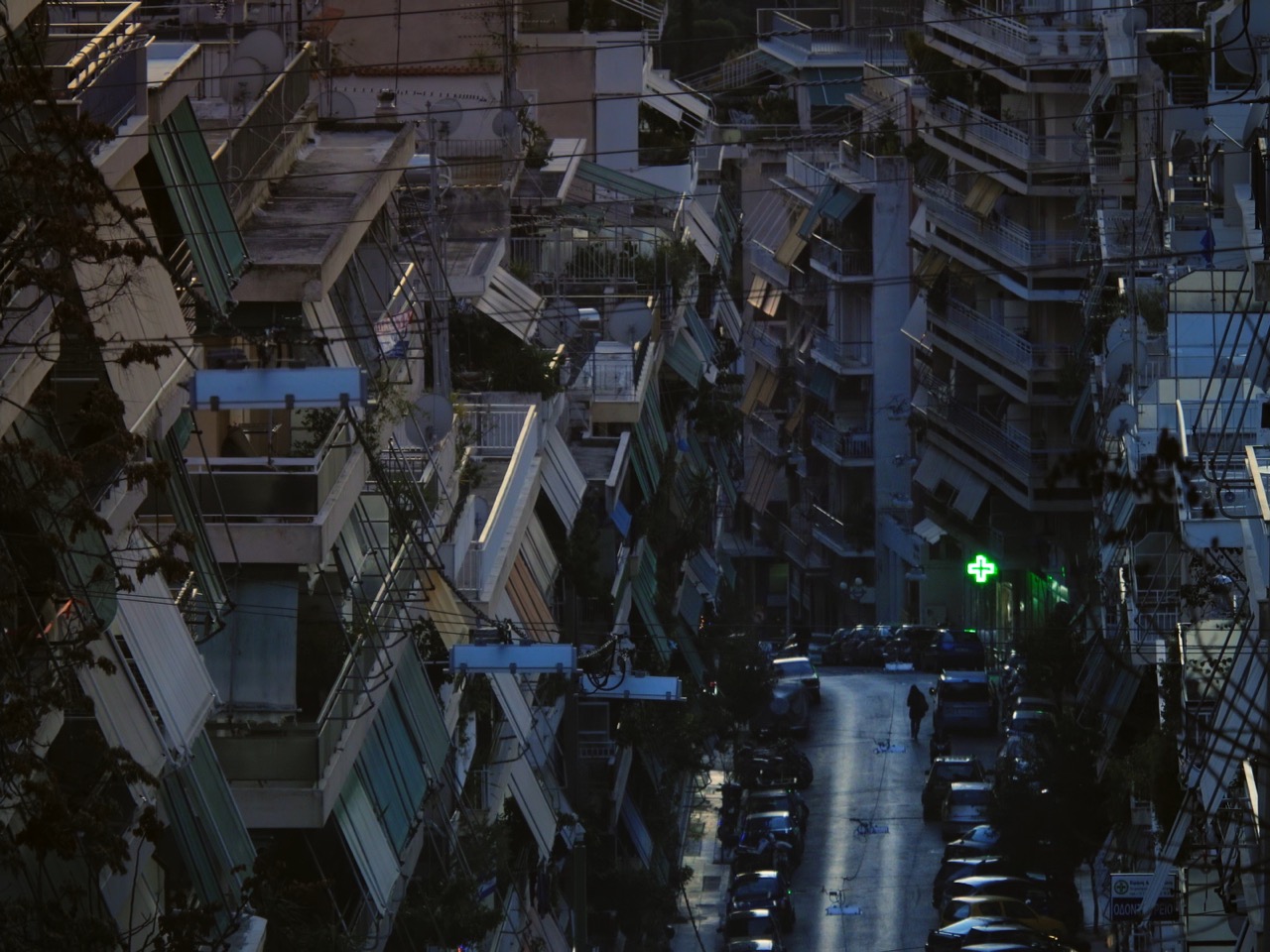

In 2015 and 2016, I collaborated with various participants and organizations associated with the grassroots solidarity movement in Athens. During our conversations, I was struck by how difficult it was to agree on words that did justice to the lived experience of solidarity work. It felt as though words could not grasp the scale of the particular imaginary that inspires the daily work of making the world anew, producing eloquence, intelligence, and creativity in the midst of the brokenness of the present. This experience prompted me to explore these “poetics of solidarity” in a film, Under These Words (Solidarity Athens 2016) (2017). In this text, I share my reflections upon both the film and the process of its making.1

close to each other

Since 2012, many groups of local activists and ordinary citizens have kick-started solidarity structures all over Greece, organizing resistance around the basic needs of the people in their communities. They have reconnected electricity, organized the distribution of agricultural products minus the middlemen, and established solidarity healthcare clinics and tutoring programs.

The more distant roots of this movement can be traced to the anti-globalization movement that has been active since the early 2000s, to the efforts to defend public spaces undertaken by local communities, to the growing culture of self-organized social centers, and to the “no pay” campaigns such as those targeting road tolls. However, the transformative experiences that ultimately triggered the rise of the solidarity movement were the multitudinous struggles of the popular collectives against the EU Troika and the bailout programs, especially the “Movement of the Squares” during the summer of 2011. This genuinely grassroots movement played a pivotal role in popularizing a culture of self-organization, people’s assemblies, and direct democracy as a tool for decision-making processes.2

From an international perspective, the Greek occupation of the squares in 2011 can be seen as part of a then-larger wave of global unrest that can be gathered together under the umbrella term of encampment movements. As Valeria Graziano points out in her essay “Prefigurative Practices,” the social movements that were developing individually as part of these different occupations very well “understood power as a diffused force ubiquitously present in social formations, and were therefore much more attentive to creating and sustaining forms of direct democracy, consensus building, and diffused self-organization.”3 Moreover, as Graziano argues, there is an aspect of “prefiguration” in the practices they developed, in the sense that these movements were practicing an “ethos of seeking congruence between the means and the ends of political action,” summarized in the expression “be the change you want to see.” In doing so, the social movements “foregrounded the necessity of a deeper change in all kinds of social relations.”4 In the Athenian context, the occupants would continue their prefigurative practices after the disassembly of the squares by building self-initiated solidarity organizations as they are manifested today: clinics, pharmacies, kitchens, food redistribution centers, schools, and so on.

After a series of encounters throughout 2015 and 2016 with different participants from a varied set of Athens solidarity organizations, I gradually became interested in a cinematic staging that would transmit the imaginal life of these networks of popular participation.5 Although my orientation would result in some kind of portrait, or rather several portraits of different people and organizations, I never had the assumption that any result could be adequate in terms of documentary representation. My intention during the process was to make another quality appear—a cinematic suggestion of the practical consciousness and social conviviality I had experienced during my visits. The daily practices of care and situated methods enabling equality for all people in and around these organizations built up to a very tangible and sensuous social space that I wanted to frame and reproduce within a cinematic space of appearances. Rather than gravitating toward a somewhat journalistic approach, it seemed to me that a documentary and fiction hybrid would grant more possibilities to bring attention to the texture and skin of this—here, now, and alive—the active contemporaneity of the lives lived in these organizations. Following on from this, I decided to engage a trio of professional actors—Evi Saoulidou, Christos Passalis and Bryana Fritz—who would embody the position of those that arrive unacquainted to the movement, just like me, initially, or just like most viewers of the film. As a result, the encounter became the film’s leitmotiv, and the social movement’s adage “close [to] each other”—the original Greek expression αλληλεγγύη (allilengýi), translated into English as “solidarity”—turned into an incentive for our hands-on heuristic method employed during the film process, both practical and micropolitical.

As I’ve learned during this endeavor, a social movement such as the solidarity movement in Athens initiates a process that delineates the transformative potential for changing the form and nature of a society’s activities in the deepest structure of its relationships and feelings. In case of a benevolent intention to reproduce any of this, the “specific feelings, specific rhythms” of the movement’s “specific kinds of sociality” wrest an attentive care from those that try to do so, preventing any kind of easy extraction—something that we experienced during the filming process.6 In fact, it is inconceivable to reduce to a formula the social experiences and ambiences that build up to the specific kinds of sociality that constitute the space of appearances within this social movement. After all, as Alberto Toscano asserts in his essay “Politics in a Tragic Key,” “the process of revolution, of transition—with its material pressures, its actually contradictory but in themselves legitimate demands, its superimposition of multiple temporalities of accumulations and subjectivation—could be conceived as ineliminably tragic,” resulting in the “absence” of any form “of reconciliation.”7 Therefore, as Raymond Williams acknowledges, “all the known complexities, the experienced tensions, shifts, and uncertainties, the intricate forms of unevenness and confusion” that invoke the contradictory vicissitudes within a social movement “are against the terms of the reduction.”8 From this awareness, Williams proposes a “cultural hypothesis” that would enable us to identify the “specific qualitative changes” of emergent and wavering social experience as “changes in structures of feeling”: “We are talking about characteristic elements of impulse, restraint, and tone; specifically affective elements of consciousness and relationships: not feeling against thought, but thought as felt and feeling as thought: practical consciousness of a present kind, in a living and interrelating continuity. We are then defining these elements as a ‘structure’: as a set, with specific internal relations, at once interlocking and in tension.”9

Following this through, if I want to approach the realm of experiences and social practices of a social movement, I must come up with a method “that is attentive to what is elusive, fantastic, contingent, and often barely there,” as Avery F. Gordon has been advocating in Ghostly Matters.10 Specifically, Williams’s hypothesis can help us to understand and explore the structures of feeling that have conjured up the movement’s call for a social transition, for a collective questioning of what an equally livable life should be.

sensory organs for the alternative

As Gordon expounds in Ghostly Matters, the notion of haunting describes “an animated state in which a repressed or unresolved social violence is making itself known, sometimes very directly, sometimes more obliquely.”11 Something that appears removed from you or me makes its impact felt in our everyday life through the way that it causes unwanted changes. The term “haunting” elucidates the field of our unwilled receptivity, susceptibility, and, also, of our vulnerability. At the same time, Gordon continues, haunting produces the conditions and possibilities for acting, for a-something-to-be-done.12 This very domain of turmoil and trouble—and our susceptibility to it—is where our refusal or revision resides, where new formulations and calls for change, or even rupture, can begin. Haunting can thus be regarded as a particular site of mediation, where “specific qualitative changes” in social experience that “are emergent or pre-emergent, […] do not have to await definition, classification, or rationalization before they exert palpable pressures and set effective limits on experience and on action.”13

In the case of the Athens solidarity movement, the haunting resides in “the experienced complexities and uncertainties, forms of confusion, and unease” that are mostly associated in the popular media with the social, economic, and political “crisis” invoked by the bailout programs of the Troika.14 In his essay “Democracy and Catastrophe,” Toscano departs from this perspective when he seeks to “reflect on what it might mean to reframe our political thinking, and our conceptions of political organization and collective agency, with notions such as crisis and catastrophe in the foreground.” This follows from “Gramsci’s suggestion that only the preliminary construction of a collective agent can prepare for, intervene in, and if needs be accelerate the crisis of a social and economic order. What then would it mean to formulate political organization and agency in terms of crisis?” As Toscano concludes, “instead of thinking of catastrophe as a structural change that comes to undo, invariably for the worse, a tolerable status quo,” it is crucial for us to both refine our sense of “the intolerability of the present” and even to consider “the idea, broached by Marcuse, of a positive catastrophe.”15 Taking up Toscano’s proposition, we can draw further on the terms that Herbert Marcuse introduced, especially when he connects the cultivation of our sense of the intolerability of the present with an “instinct for freedom” that takes root “in the very nature, in the "biology" of the individual.”16

There is a scene in Under These Words (Solidarity Athens 2016) at Solidarity Piraeus—where hundreds of volunteers are involved in the redistribution of food, clothes, other material goods, and education—when Kostas Karras, one of the founders of the organization, explains in conversation that “[it] is fascinating to observe how a person evolves after he joins Solidarity. How they change as a person. This cannot be expressed with words, there are no words for it. […] this is what I receive. It doesn’t give me a feeling of responsibility, it’s just a clear view on things.”17 I want to bring attention to the interesting fact that Karras denounces the term “responsibility.” Is it because he has experienced how the individualizing and maddening form of responsibility induced by market-conforming self-formation has become obsolete, in favor of an ethos of solidarity that would affirm mutual dependency, dependency on workable infrastructures, and social networks, enabling the people of Solidarity Pireaus to exercise freedom together?18 In Marcuse’s terms, the “instinct for freedom,” which propels the solidarity participants, is “the environment of an organism which is no longer capable of adapting to the competitive performances required for well-being under domination, no longer capable of tolerating the aggressiveness, brutality, and ugliness of the established way of life.”19 For Marcuse, the word biology designates the process by which “inclinations, behavior patterns, and aspirations” become vital needs that if not satisfied will cause us to fall apart. The instinctual basis for freedom can and must become our “second nature.” In order to do so, we require what Marcuse called sensory “organs for the alternative.”20

From the vantage point of living in an intolerable present, the inclinations, behavior patterns, and aspirations of an organism become haunted. The alternatives are not missing or locked away in some elusive or fantastic futurity—they are already here. While this cannot be expressed with words, there are no words for it—after all, we are talking about “experiences to which the fixed forms do not speak at all, which […] they do not recognize”21 — a clear view on things emerges: “Solidarity, without realizing it, offers more than one gives.”22

solidarity poiesis

In my conversation with Avery F. Gordon and Tom Engels in the book Solidarity Poiesis: I Will Come and Steal You (2017), I explain how, during the filming, “by way of a collective process via encounters and conversations with the historical actors, the theatrical invention we ended up with was to conceive the position and role of actors-as-citizens. Here, the actors do not draw from the historical present, but are drawn into it. The turn from actor to citizen cannot be embarked on knowingly, to some extent one is confronted with an impossibility to perform.23 As Engels—who was present during the filming process—explains in our conversation, the actors’ silence appears as a leitmotiv that “thwarts a more traditional function of the actor, seen as the one who is supposed to speak or deliver and the one who takes on a role.”24

Nevertheless, during the filming process—in reality—there was more to it in Engels’s eyes. “To me, it seems that there’s an inability residing in their silence; either a silence that comes forth from a certain form of detachment, stemming from a confrontation with a situation they are not acquainted with, or a silence coming from a certain degree of shock, witnessing that the living circumstance, which the solidarity organizations try to cope with, unfortunately still unfold themselves daily. It provoked in them a situation that cannot immediately be answered by means of language. As the actors could only rely on vaguely scripted directions, their actions were not just ‘acted’. They vulnerably exposed themselves—just as everyone did in the process—to the implications of shooting a film on solidarity organizations: their actions and words had real implications.” This is the moment in which reality crashes into the script, as Engels explains. “As one can see in the film, Evi Saoulidou joins the lady from Solidarity Piraeus cutting spring onions and green peppers. They hardly converse; the focus lies on cutting vegetables. However, when that take was finished and the next scene was scheduled, Saoulidou refused to continue the shoot and said she only would do so when the box of green peppers was empty. Some of the crewmembers joined her until every single green pepper was cut. This is the moment in which that gesture becomes action and not just an image of action.” As Engels argues, what had happened is that, “to surpass the silence, all she could do was to lend her body to what had to be done: the cooking of food. Silence, or the difficulty to speak, was overcome by gesture, by action, by concrete support.”25

Engels’s observation brings to mind how all consciousness is social, how its processes occur not only between but within the relationship and the related. For instance, my body is constituted through perspectives it cannot inhabit; someone else sees my face in a way that I cannot and hears my voice in a way that I cannot. I am in this sense—bodily—always over there, yet here, and this positive version of dispossession marks the sociality to which I belong. I see here that, during our filming process, an experience of inability within the scripted encounter had incited the actress Evi Saoulidou to crash through the image of relation into a tangible act of concrete support, one which deviated from the script, the image, the role she was supposed to play. This is an example of what I call “solidarity poiesis.” As participants of the solidarity organizations know very well, at the heart of true equality, status is not worked out in advance or outside relation. During the filming process, on both sides of the camera, everyone “vulnerably exposed themselves.” Lending oneself to “raw” social exposure—beyond merely acting a role—usually leads to a breach of protocol, to a rupture of established, preconceived or imagined distinctions. In very much the same way, the making of freedom during the occupations of the squares implied a disaffection with conventional distinctions between public and private, making all daily actions within this space of appearances political.

During the rehearsals Saoulidou explained to the other actors and I how acting works for her: “I think that the spectator doesn’t hear the words of what you say. He or she hears something else that connects the words, […] it’s under the words.”26 During the editing of the film, I superimposed these words spoken by her as a voice-over for the scene where she joins the woman from Solidarity Piraeus cutting vegetables. This moment, one where she’s pondering a something-to-be-done, stirred by a sensation of inability, summoned the urge to redefine or rework her poetics during the acting process. By bringing a voice-over and a scene together in this way, I am making a suggestion. This feeling that what usually matters is beyond words, combined with the inclination to crash the script with an action beyond the image of action, here delineates a structure of feeling, one that, as a new kind of infrastructure in its own right, “articulates” the “presence” of a shared sociality.27 This is “production into presence,” in alliance with the original, Aristotelian conception of poiesis – ποίησις (poíisis).28 For me, this is how a poiesis that departs from the reality principle of being “close [to] each other”—αλληλεγγύη (allilengýi)—works.

as a way of ending it

Now, as Williams insists, it is imperative to define “forms and conventions in art and literature as inalienable elements of a social material process: not by derivation from other social forms and pre-forms, but as social formation of a specific kind which may in turn be seen as the articulation (often the only fully available articulation) of structures of feeling which as living processes are much more widely experienced.”29 Hence, in order to avoid veiling or suppressing its inextricability from social material processes, such social formation of a specific kind must insist on making common cause with the social sphere.30 In her essay “Partisan Welfare—Group Phantasy as Social Infrastructure” Graziano asks: “What would it mean for practitioners to re-valorize art and culture, not as kinds of specialized production, but as elements of a broader process of partisan social reproduction?” Hereby she proposes—taking inspiration from the prefigurative practices of social movements—a congruency and a resonance” between ways of “organizing social reproduction and production,” incorporating “tactics for an effective political resistance.”31 By self-organizing the much needed conditions for an equally livable life, a popular assembly does not only take power over its own means, it also gains some release from the suffocating hold of the dreadfully passive view of politics that the “established way of life” upholds.32 This does not only generate new practices and imaginations of emancipation, but consequently involves a daily collective work toward an alternative conception of property, selfhood, and social life. I agree with Graziano that forms of social reproduction in the arts—social formations of a specific kind—can also take part in such prefiguration, producing truth-games, forms of imaginal feedback, and heuristics for learning and testing.

Furthermore, I believe it’s good to focus on elucidating the often complex structures of feeling that are conjured up in this context, which, if we consider these as social infrastructures of their own kind, can be generative for a deeper understanding of our social experiences as infrastructure at large. However, as the dramaturge and theatre maker Goran Sergej Pristaš warns with regards to an argument made by Stephen Zepke, contemporary artistic practice appears to be at “a particular low point in creativity and insurrectionary spirit, not least because ‘resistance’ is now aggressively marketed as one of art’s selling points.”33 This is due to a systemic tendency toward “anti-production” within the arts, actively subsuming the social relations and politics of artistic work to the larger spheres of productive activity (praxis), including a fetishizing of the artistic process in its performative demeanor, which in turn causes it to haunt the sites of artistic production (poiesis).34 There is a risk that poetics, as the art of making new “forms of approach” on the basis of exposure to the differences and distances that make up our sociality, slides out of view. Moreover, as long it remains inscribed within a socio-economic culture of sovereign-style individualist virtuoso labor, alliances with scenes and sites of collective and turbulent social production are actively discouraged.

To conclude, I believe it is crucial to enable a poetics that generates infrastructures of their own kind, ones that can be seen as sensuous, “non-reproductive” extensions of our sociality.35 After all, that which can be deemed crucial for imagination is the sensuousness that imagination is operating with: the resistance of the concrete to any form of abstraction or reduction.36 For an imagination to inspire something other than a submissive, depoliticized, and flat way of being in the world, for an imagination to give way to our sensory organs for the alternative, a raw exposure toward distance within relations of equality must be maintained. However, the forms, notes and proposals orientated toward such a poetics are too often allowed to pass for its actual pursuit. If we want artistic production to mediate structures of feeling that actively induce our sense of the intolerability of the present, we have to refine and cultivate our capabilities to continuously reside and create in prefigurative muddy waters: inside the distance within the social relationship and the socially related. One doesn’t need “to go out into the streets,” as the expression goes, because we’ve been on the streets all along, all this time. Common ground within sociality is not to be found in an image of reconciliation—that of conviviality—but rather in acting from the condition of a lived interdependency, conjuring up an active and concrete participation in disorder, as a way of ending it. In my view, what comes before everything else is inciting what I refer to here as solidarity poiesis: a poetics that remains bound to the social reality it is originating from, intent on reproducing its own infrastructures to think and act against the intolerability of the present, and taking bodily vulnerability within social relation as its inalienable reality principle.

- 1. This text is a re-edit of key excerpts from the opening essay of my book Solidarity Poiesis: I Will Come and Steal You (Berlin: b_books, 2017), which can be seen as a parallel work, one that helps us to think through some of the questions that were present during the making of the film.

- 2. Solidarity for All, Building hope against fear and devastation (Athens: Solidarity for All, 2015), 13–14.

- 3. Valeria Graziano, “Prefigurative practices: Raw materials for a political positioning of art, leaving the avant-garde,”, in Turn, Turtle! Reenacting The Institute, ed. Elke Van Camout and Lilia Mestre, (Alexander Verlag and Live Art Development Agency, 2016).

- 4. Ibid.

- 5. I had initial encounters in 2015 with a broad range of organizations, and, after that, more focused meetings and conversations throughout 2016 with the Community Clinic of Hellenikon, the Solidarity School Mesopotamia in Moschato, the Solidarity Pharmacy of Patisia, and the food solidarity organization Solidarity Piraeus.

- 6. Raymond Williams, Marxism and Literature (New York – Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1977),133.

- 7. Raymond Williams, Modern Tragedy (London: Verso, 1979), 81 via Alberto Toscano, “Politics in a Tragic Key”, in Radical Philosophy, 180 (July/August 2013)32, emphasis by the author.

- 8. Williams, Marxism and Literature, 129.

- 9. Ibid., 132.

- 10. Avery F. Gordon, Ghostly Matters: Haunting and the Sociological Imagination (London – Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1997), 26.

- 11. Gordon, Ghostly Matters: Haunting and the Sociological Imagination, xvi.

- 12. Ibid., xvii; Moreover, Gordon has been putting this argument into practice by taking the following statement by Herbert Marcuse as an epistemologically instruction: “Social theory is concerned with the historical alternatives which haunt the established society as subversive tendencies and forces. The values attached to these alternatives […] become facts when they are translated into reality by […] practice” (Avery F. Gordon, “Some Thoughts on the Utopian,” in Keeping Good Time: Reflections on Knowledge, Power, and People (Boulder - London: Paradigm Publishers, 2004), 126.

- 13. Williams, Marxism and Literature, 132.

- 14. Ibid.

- 15. Alberto Toscano, “Democracy and Catastrophe,” in: Solidarity Poiesis: I Will Come and Steal You, ed. Robin Vanbesien (Berlin: b_books, 2017), 31-43.

- 16. Herbert Marcuse, An Essay on Liberation (Middlesex, England: Penguin Books, 1973), 26, via Gordon, “Some Thoughts on the Utopian,”124.

- 17. Under These Words (Solidarity Athens 2016), directed by Robin Vanbesien, (2017).

- 18. See also: Isabell Lorey, State of Insecurity. Government of the Precarious, trans. Aileen Derieg (London – New York: Verso, 2015).

- 19. Marcuse, An Essay on Liberation, 14m via Gordon, “Some Thoughts on the Utopian,”124, emphasis my own.

- 20. Marcuse, An Essay on Liberation, 20 and 26 via Gordon, “Some Thoughts on the Utopian,” 124.

- 21. Williams, Marxism and Literature, 130.

- 22. Vanbesien, Under These Words (Solidarity Athens 2016).

- 23. Tom Engels, Avery F. Gordon and Robin Vanbesien, “I Will Come and Steal You: A Conversation”, in Solidarity Poiesis: I Will Come and Steal You, ed. Vanbesien, 58-85, emphasis by the authors.

- 24. Ibid.

- 25. Ibid.

- 26. Vanbesien, Under These Words (Solidarity Athens 2016), the film’s title is based on these words of Saoulidou.

- 27. Williams, Marxism and Literature, 135.

- 28. Giorgio Agamben, Man Without Content, trans. Giorgia Albert (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1994),45.

- 29. Williams, Marxism and Literature, 133, emphasis mine.

- 30. See also Gordon, Ghostly Matters: Haunting and the Sociological Imagination, 21.

- 31. Graziano, “Partisan Welfare – Group Phantasy as Social Infrastructure,” in Solidarity Poiesis: I Will Come and Steal You, ed. Vanbesien 102–103.

- 32. Marcuse, An Essay on Liberation, 14 via Gordon, “Some Thoughts on the Utopian.” 124.

- 33. Stephen Zepke, “Schizo-revolutionary Art; Deleuze, Guattari and Communication Theory.” in Deleuze and the Schizoanalysis of Visual Art, ed. Ian Buchanan and Lorna Collins, (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2014), 37 via Goran Sergej Pristaš, “Anti-Production of Art”, in Commons/Undercommons in Art, Education, Work …, eds. Bojana Cvejić, Bojana Kunst, and Stefan Hölscher, TkH, Journal for Performing Arts Theory, No. 23 (2016) 31.

- 34. The tendency to reproduce artistic labor as an alternative to the production of artworks, with the (cl)aim to destabilise a fetish of objects, has actually turned into a fetishization of process where the so-called free, non-alienated artistic work became a usable good, thereby erasing a difference between artistic production (poiesis) and reproductions of modes of production.” (Pristaš, “Anti-Production of Art,”30.)

- 35. Lauren Berlant, ‘The commons: Infrastructures for troubling times’, in Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 34.3 (2016) 393.

- 36. Michael Taussig takes up Walter Benjamin’s notion of the ‘mimetic faculty’ along these lines, in: Michael Taussig, Mimesis and Alterity. A Particular History of the Senses (London – New York: Routledge, 1993).